Anyone who regularly visits facebook.com may be familiar with

this ad. I've been bothered by some American Apparel ads before, but haven't yet complained about the company on this website. Fortunately for me, I found a wonderful piece on American Apparel that perfectly captures what I originally aimed to articulate myself.

Besides the fact that I don't like American Apparel,

the ad caught my eye because the girl looks to be about 12. For a second, I thought maybe I was wrong and/or overreacting. But I clicked on the ad, and the URL included the word "tweener," referring to a pre-teen. Personally, I find this swimsuit a bit revealing and the pose too sexualized for a pre-teen. It seems pretty clear they are trying to make this model look "sexy," and I don't think that's right for a 12 year old.

I went on to do a bit of investigative work (at least that's what I like to call it to make myself feel important), and I visited the official American Apparel website to check out their photographs. To my relief, their was no highly sexualized "tweener" photograph section. In fact, I found galleries for adult clothing and children clothing, but no teen section. Not only did I not find a teen or tween section, but in no place did I see the offending ad, the same model, or even the same swimsuit! So, why is this weird ad on facebook.com all the time

? Most people who use facebook are definitely not in their preteen years.

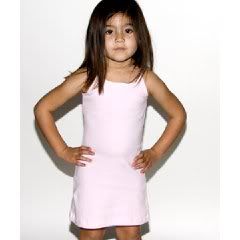

Well, since there's no teen section to rip apart on the American Apparel site, let's take a quick look at the kids section. Here are some pictures from the kids skirt/dress section:

The above "dress" also "doubles as a long tank top," according to the website. Why is that? Because there is not enough fabric here for a dress! Sure, I've seen worse, but there is a bigger picture here, and that is that we are increasnigly seeing sexy clothes being marketed and sold to kids. What do you think?

This skirt is advertised as being "a short yet modest style." If I had a young daughter, I would never buy a skirt that short for her.

And finally, I present the wonderful article I mentioned earlier. It is actually part of a

much longer piece, and for those who are so inclined, I highly recommend reading the whole thing via the link provided. Otherwise, dig in:

Love for Sale: Criticism and Defense of Advertising

by Bernard Dolan, Special to Knowmore.orgAugust 22, 2006

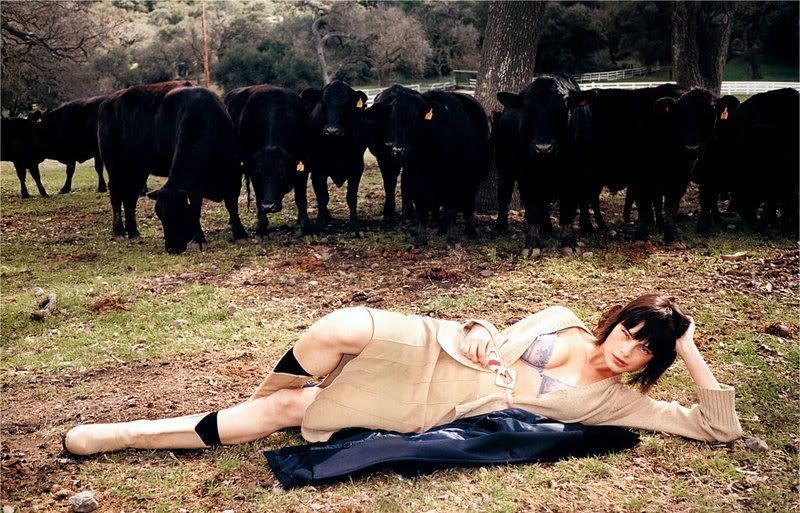

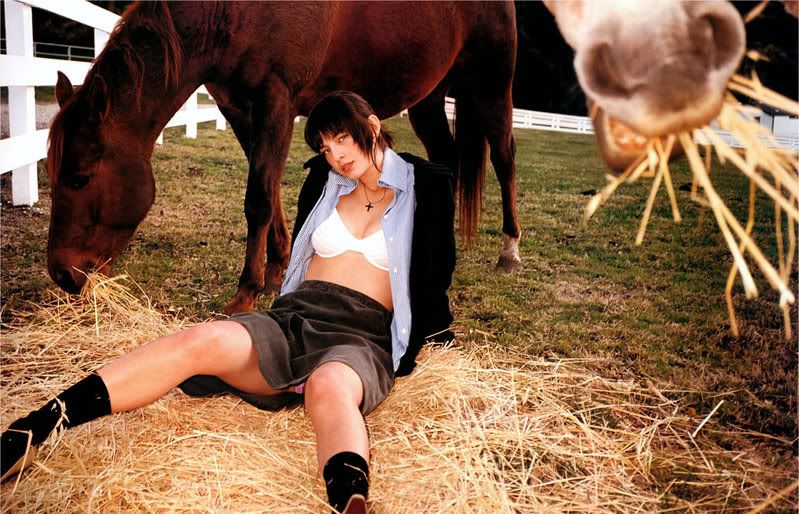

In 2005, Jason Rowe, a columnist for NYU’s Washington Square News, described American Apparel's ads as, “Photographs of young women in compromising positions, some as young as fifteen... juxtaposed alongside text giving accounts of meeting the models on the street and inviting them to be photographed... conveying the feeling of some sort of perverted conquest." Rowe called the ads "sexually exploitative" and noted that they "seem more like amateur pornography than anything else."

As American Apparel's slinky ads have spread across urban landscapes, the internet, and the pages of weekly culture rags, many commentators have begun to voice similar criticism. The ads have been compared to child pornography, called "sleazy" and "creepy," and have constantly been linked with Charney's rumored sexual antics and legal battles.

In a 2005 interview with NowToronto.com, Media Watch founder Ann Simonton called for a boycott of American Apparel products over the ads. "This is beyond 'sex sells,'" Simonton told the interviewer. "It goes to a level of humiliation."

And yet the same NowToronto article found Charney's ads being defended, by porn star turned PhD sexologist Annie Sprinkle.

"I like the sweat, the grit, the reality," Sprinkle said. "He obviously appreciates female sexuality in all its glorious sleaziness. And I think you can worship female sexuality and also worship women in the workplace. If you see sex as bad, dirty, and ugly, then you're going to see these ads as bad, dirty and ugly. These ads are kind of a mirror. In a way, they're almost neutral."

I spoke with Alexandra Sprunt, head of American Apparel's marketing department, about the ads. Ms. Sprunt echoed Annie Sprinkle's defense, explaining that many of the controversial photographs used for the ads were culled from "random shots" taken by a number of employees and their friends.

As evidence of this "random" motif, which she claimed Charney created in the company's early days, Ms. Sprunt showed me an American Apparel print ad featuring a picture of an elderly couple in Montreal, and another featuring a car's bumper in the company parking lot.

She also singled out ads featuring photos she and her friends had taken, and told me the back-stories behind some of the images.

"If you saw this without knowing where it came from you might just think it's a dirty picture I guess," she said of one photo. "But to me that's a great picture from a funny night that sort of captures what me and my friends do when we hang out."

This is a central feature of the company's defense of its advertising: that the ads it uses are the natural outgrowth of a genuine youth culture at the company. In defense of their advertising, company representatives often point to a "sexy lifestyle" being lived by the company's employees, from which the ads spring spontaneously. The company goes so far as to include a "gallery" section on its website, featuring collections of amateur photography by employees, videos of photo shoots and office Christmas parties, and other pieces of what the site calls "American Apparel Culture". In a way then, American Apparel wants its ads to be viewed as spontaneous art, produced by and among its employees, featuring its employees.

But isn't there a difference between art and advertising? And what about those who don't want to participate in American Apparel's sexy "youth culture"? Isn't there still something basically irresponsible in plastering city buses and park benches with pictures of spread eagle girls blowing bubblegum, for the sake of selling t-shirts?

In my conversations with American Apparel's press agent, Cynthia Semon, she acknowledged that the ads are just that: advertising. They are created in a prescribed way, to appeal to a targeted audience with the aim of selling goods to that audience. In this way, they are funadementally different from art created for art's sake.

However, Ms. Semon still defended the company's ads by comparing their critics to those who would censor erotic art.

She and American Apparel assert that it is the viewers individual responsibility to curb the harmful societal trends blamed on advertising and art. Parents should educate their children about sex and raise them properly, she maintains; advertisers should not be faulted for selling their products as they see fit. "No corporation can influence a child more so than their family," she said.

Many critics of advertising disagree. In her book Can't Buy My Love: How Advertising Changes the Way We Think and Feel, author Jean Kilbourne takes exception to the kind of 'individual prevention only' approach to social problems that Ms. Semon is advocating. Kilbourne argues that there is a need for a more widespread, "systems approach" of regulating businesses and advertising if people are to curb the social problems they are linked to. She writes:

- "People make choices, for better or worse, in a physical, social, economic, and legal environment. The credo of individualism and self-determination ignores the fact that people's behavior is profoundly shaped by their environment, which in turn is shaped by public policy. Certainly individual behavior and responsibility matter, but they don't occur within a vacuum. ...

- The systems approach is easily misunderstood because some of the interventions can seem trivial, especially in light of the extent of the problems. When some parents in a Boston suburb complained about an advertisement for beer in a Little League field, a well-known Boston columnist ridiculed them as "touchy-feely, politically correct busybodies" who thought the ad would immediatly "turn their kids into drunks."... Like a lot of people, he completely missed the point. Which is that we give a message to our children about the normalcy of beer-drinking and about societal expectations when we allow such an ad on a Little League field. A single ad-or scores of ads- won't turn kids into drunks, but they are part of a climate that normalizes and glamorizes drinking, and research proves that this especially effects young people.

Ms. Kilbourne writes that where a focus on individual prevention has failed to curb social problems like drinking and tobacco use, systems approaches have succeeded dramatically.

She uses as an example the history of antismoking organizations, who for years focused on the individual smoker as "the problem," offering consumers health information, pictures of diseased lungs and advice for quitting. Data showed, however, that an individual prevention approach was not improving public health. Antismoking organizations then began switching their strategies, highlighting the role of the environment and the institutional responsibility of the tobacco industry. Bans were placed on cigarette advertising and promotion, aggressive counteradvertising was created, and higher taxes and better warning labels were placed on cigarettes.

As a result of this shift to a systems approach, consumption of cigarettes has plummeted in states that launch aggressive anti-tobacco campaigns, and the norms for cigarette smoking have changed dramatically in the past 20 years.

But do ads that use sex to sell contribute significantly to a harmful environment? A number of academics, activists, and consumers seem to think so.

Mallory Hanora, a feminist and contributor to Knowmore.org, had the following to say about American Apparel's ads:

- "American Apparel is built not only on what it sells, but how it sells it. If worker's rights are truly important to the production of a t-shirt, why isn't the objectification of female models important in the process of selling that t-shirt? After all, the models in American Apparel's advertisements are part of the company's workforce. For a so called visionary company, it's hypocritical and shortsighted to trumpet the influence you have over labor policies in garment manufacturing, but deny that same influence over marketing by submitting to the sexist, exploitative status quo in advertising."

With the help of Alexandra Sprunt and Cynthia Semon at American Apparel, I compiled a diverse collection of about 80 of the company's ads from the past two years. The ads were then shown to Dr. Susan Bordo, Professor of Gender and Women's Studies at the University of Kentucky. Dr. Bordo is the author of numerous books involving gender, cultural images and their relation to body image issues, including Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. She had the following to say about American Apparel's advertising:

- "My biggest complaint against ads such as these is the way they get away with soft-core porn body postures and motifs -- for example, spread legs and orgasm-like facial expressions, done in an 'unposed' polaroid-type style -- under the guise of being 'young, fresh, and authentic.' The marketers use post-modernism and 'youth culture' ideology as an excuse for moving the bar lower and lower regarding what is acceptable to show. Calvin Klein was the first to employ this strategy in his famous 1994 series of TV ads, which looked like home movies with underage models, and which were ultimately yanked from the air. Klein defended the ads by saying the models weren't actually underage (as though that were the issue) and by insisting that for him they had less to do with sex than with spontaneity and youthfulness. The idea: These young people are simply being 'natural'; it's the sleazy-minded viewers that see the dirty sex in the ads.

- The reality of imagery is, however, that the more stylized and polished photos are -- the more 'high fashion' drama they express -- the less pornographic they look. In the posed, glossy, and highly stylized photos of most (not all) fashion spreads, the models do not look like they've been caught unaware or don't fully understand the meaning of what they're doing. They look like models. These American Apparel ads, in contrast, which pride themselves on using 'real people,' for that very reason have a much more pornographic edge to them.

- It's distressing that the same kind of images that had to be taken off TV in 1994 are, in 2006, are stuff of 'left-wing' advertising!

- Do the images have an effect? All you have to do is walk down any suburban street and you'll see the answer to that. Six and seven year olds, who don't have any real idea of what they are doing, are aping the poses, the gestures, the personae. Young, fresh, and spontaneous? Or little girls learning how to play by the current rule that if you aren't sexy, you aren't worth anything?"

Charney remains dismissive of those who would criticize his company's ads. In our conversation, Dov pointed to soaring profits as evidence that "the average consumer doesn't care about this stuff. Most people are responding to our ads. All of this criticism is academic. ... It all comes down to personal taste. Look it's not like I'm selling beer, you know. We're selling sexy underwear, so we have sexy ads!"

by Bernard Dolan, Special to Knowmore.orgAugust 22, 2006***

"All of this criticism is academic." That's just brilliant. But, really, I shouldn't be suprised that Dov Charney fails to understand. After all, he seems to enjoy using his own body to try to sell his product.

Yeah, that's the CEO of American Apparel himself. And that picture is supposed to make me want to shop there?! I would think they'd put this ad up in the window if they were trying to keep people

away, especially if you know anything about the guy.